There are people in the world who naturally think and converse in a linear manner – a sequential series of observations or opinions, one forming neatly in front of the other, as an impenetrable chain of command. And society needs these people. They keep the trains on the tracks, so to speak.

Anna Pogossova does not fall into this category. Rather, the Sydney-based photo media artist’s mind works in a series of enthralling loops and bends; conversation propelling forward in multiple directions as though a rabbit careening down a nearby hole. By the time an answer is finished you realise you are in a place far from the question you first asked. It’s a wonderful insight into the mind of one of our country’s most dynamic creators. For, despite all those trains that must be kept on tracks, society needs wide-lens thinkers, too.

Much like her mind, Pogossova’s portfolio traverses multiple mediums. “The outcome in the end might be an image, or something to do with an image, so I like to keep it broad,” she says.

“The outcome in the end might be an image, or something to do with an image, so I like to keep it broad.”

Anna Pogossova

"The outcome in the end might be an image, or something to do with an image, so I like to keep it broad.”

Anna Pogossova

Born in Moscow (“Which is probably the most interesting thing about me,” she laughs), Pogossova and her family migrated to Australia when she was 10. “I remember … the heat; I was walking away from the plane and I thought what I was feeling was the exhaust,” she explains. “You know when you get off the bus or something like that and you still have that residual heat? And I kept walking and walking, and the heat didn’t dissipate and I thought, ‘Oh no, that’s really what the air is like here’.”

Another observation: “Everywhere was carpeted! It was really odd.” A jarring contrast to the wooden, linoleum or tiled floors she was accustomed to in Russia, but it’s this capacity to hone-in on the minutia that makes her signature still-life work so engaging.

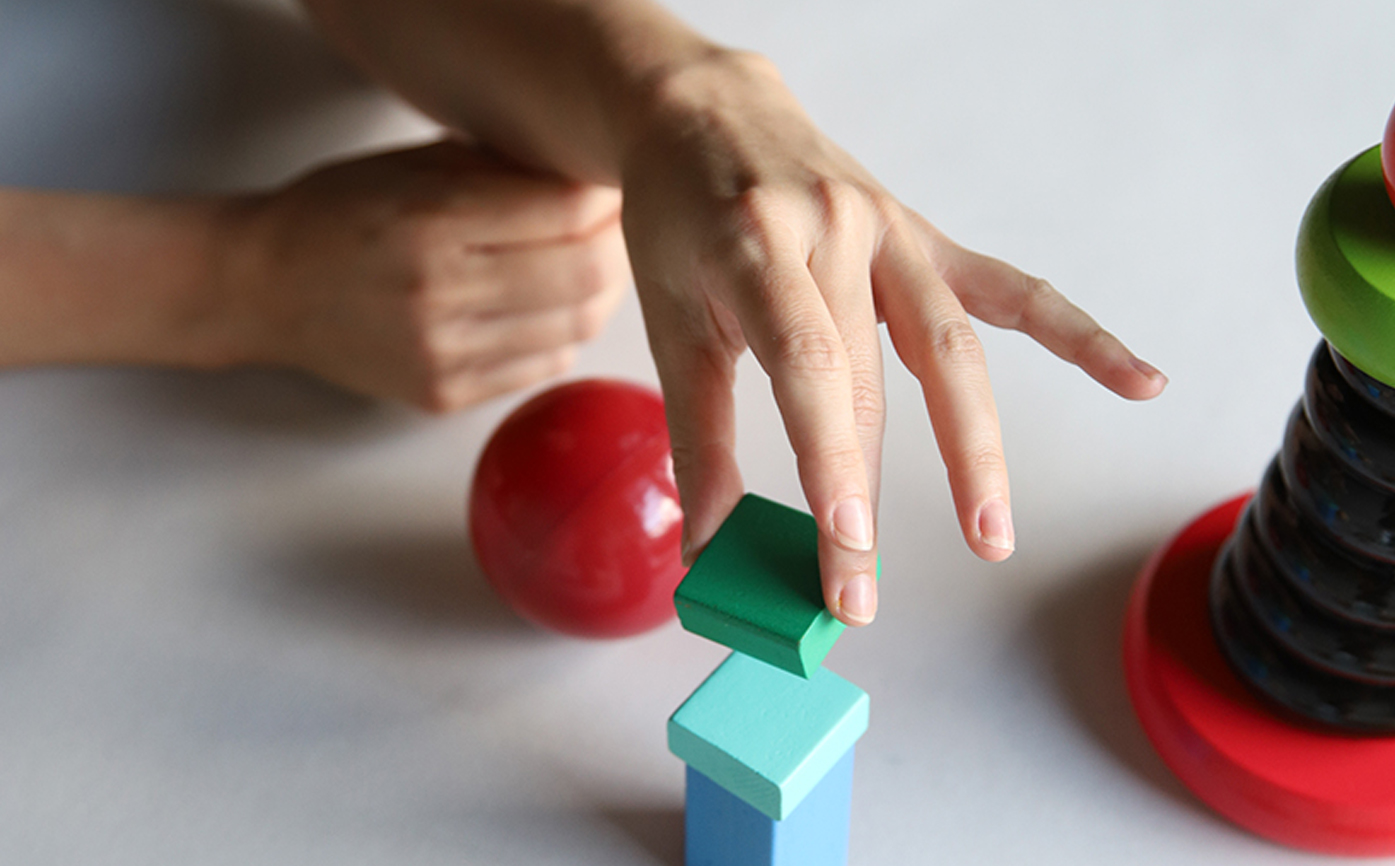

The list of editorial publications she has been commissioned by reads like a rollcall of Australian media: Vogue, RUSSH, 10, Doingbird, Museum, the AFR; her commercial client list even longer. The appeal is obvious – Pogossova’s rigorous process, her command of space, and her exploration into the mythology of objects manifest in intelligent, cinematic works that challenge the viewer to look at the ordinary from an extraordinary perspective.

“It’s really about symbols,” Pogossova explains. “That’s the simplest way to put it. It’s about the way we’ve built up the visual language of our world, and there are certain cues and objects.”

“Because they’re usually man-made, they’re essentially kind of like language. They have all these kinds of added associations and values onto them, so they’re not just a thing. They’re metaphors – symbols of other things. A combination of these objects says something more than what you’re really seeing. That’s what I’m interested in.”

It’s for this reason that she has gravitated towards the stationary, as opposed to the living and breathing, as her ideal subjects. Though, she’s quick to point out, “[objects are] kind of a direct reflection of us because we made them, and they just inherently contain all our desires and ideals, whether we think so or not.

“Someone who makes an object has something in mind for its use, and how they want it to feel. They’re feeling some kind of gap in the world and it represents something. It’s like a word, objects kind of transcend. Whereas people come in with their own agenda, they’re autonomous, they’re not the same.”

“[objects are] kind of a direct reflection of us because we made them, and they just inherently contain all our desires and ideals, whether we think so or not."

Anna Pogossova

“[objects are] kind of a direct reflection of us because we made them, and they just inherently contain all our desires and ideals, whether we think so or not."

Anna Pogossova

Pogossova ruminates on the ways her childhood, spent so far away from her now home of Sydney, bleeds into her current practice. “They’re not always super obvious, I’m not always super aware of them myself… just certain little props that remind me of things that we have at home that you don’t really see much over here.”

In fact, it was an exhibition visit years ago that drew her attention to the synchronicity of her practice and the work of other Russian photographers. “It was all kind of surreal, when I went there and I saw the images, they really resonated with me,” she recalls. “There must be something about us, there must be some similarity, because how can people on opposite sides of the earth produce similar work?”

"I actually paint in photoshop – I can paint something from scratch using the data in an image. Or you can scan something, you can use an object to imprint on a sensitised surface without a camera at all...there are so many ways to make a photographic image.”

Anna Pogossova

"I actually paint in photoshop – I can paint something from scratch using the data in an image. Or you can scan something, you can use an object to imprint on a sensitised surface without a camera at all...there are so many ways to make a photographic image.”

Anna Pogossova

The biggest misconception about her photo media art? That you have to use a camera. “For example, I actually paint in photoshop – I can paint something from scratch using the data in an image. Or you can scan something, you can use an object to imprint on a sensitised surface without a camera at all. And I think people forget about that – there are so many ways to make a photographic image.”

"I went on a path of research at one point about the nature of creative practice and how much of it is intentional, and how much isn’t. And if it’s not intentional, where is it coming from?”

Anna Pogossova

"I went on a path of research at one point about the nature of creative practice and how much of it is intentional, and how much isn’t. And if it’s not intentional, where is it coming from?”

Anna Pogossova

Talking with Pogossova about her practice leads naturally to an examination of self. She shifts mercurially between fastidious control and gut instinct – her perfect capture lying somewhere in the mid-point between the two. “I think about this a lot actually. I went on a path of research at one point about the nature of creative practice and how much of it is intentional, and how much isn’t. And if it’s not intentional, where is it coming from?

“I think it’s just in this deeper part of our psyche … It’s a different kind of brain. Like a more collective, unconscious kind of brain. As though there’s more at play than just you.”

There’s that wide lens thinking for you. And aren’t we all the better for it.

Words: Victoria Pearson

Portraits: Olivia Repaci