U: You have just launched a new podcast that is centred around stories and storytelling. What was the impetus for this project?

BL: Various people had been asking me to make a podcast for about five years—it was always flattering to be asked, but there are so many podcasts these days. I wanted to wait until I felt really confident that I would be contributing something meaningful to the audio-media landscape. I do think there is space for all kinds of podcasts, just as there is space for all kinds of books and newsletters and media, but I didn’t want it to be another single-person perspective. I also didn’t want it to be two mates having a rambling chat without some sort of focus.

I tried a few pitches and pilots in a few different ways, with different people and produced by different organisations and none worked out. Then one day my friend Bridie and I were chatting and we realised that we had really complementary skill sets and life experiences. Bridie has been on the journalism side of things more in her career. She came up through newsrooms and she’s now the opinion editor at a major news site. So, as I like to say, it’s her job to be absolutely across everything; to know both the best opinion and the most dogshit opinion on any given subject on any given week! Then I’ve got the more long-form, more analytical side—I’ve got the law thing too, and how many authors I’ve interviewed and reviews I’ve written. Also, aside from that, we just make each other laugh so much.

U: Humour is so often the cornerstone of great conversation.

BL: We do have that fun, banter, catch-up at the beginning of each episode, but then we get to talk about culture-shaping books and the best film and TV that has come out. We also talk about whatever is the biggest story of the week in Australia.The tagline is that we talk about ‘our stories, the best stories and the biggest story of the week’..

We are able—because of Bridie’s journalism experience and how involved in the news cycle we both are—to talk, for example, about what’s happening at the annual Labor conference and the effect it might have on the housing crisis. What I love most is the interaction between the daily news cycle and the multi-year cultural landscape. That’s what I value; understanding this relentless 24-hour news cycle. It can be easy to lose perspective about whether we’re making forward progress, whether we’re going backwards on issues we care about, and how much the cultural landscape has changed in the last three to five years. That affects how we hear and read news stories, and what is even being told.

I actually said to Bridie yesterday, if I wasn’t making this show I would be listening to this show.

U: Where did you first develop an interest in stories and storytelling? When did it first become significant to you?

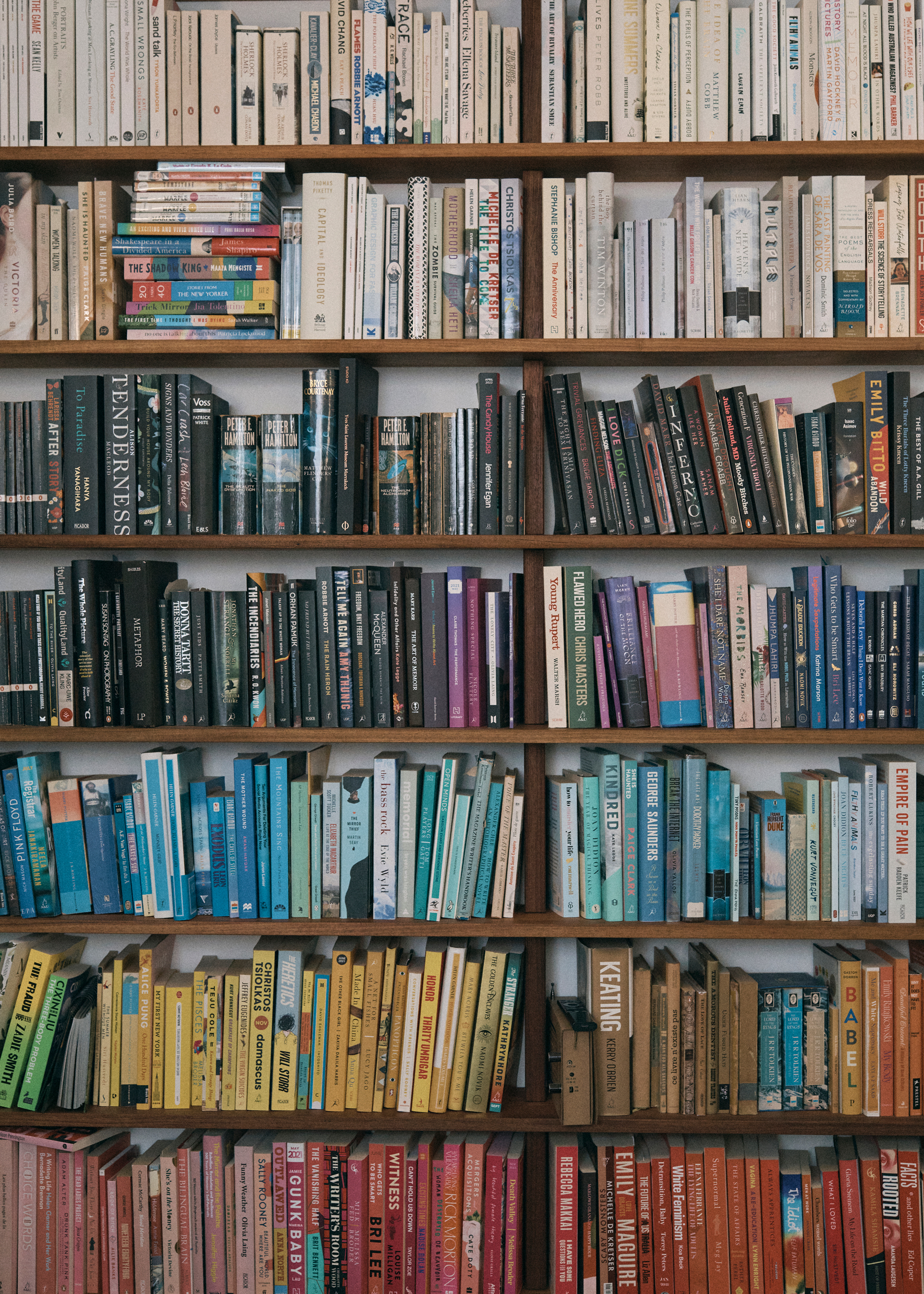

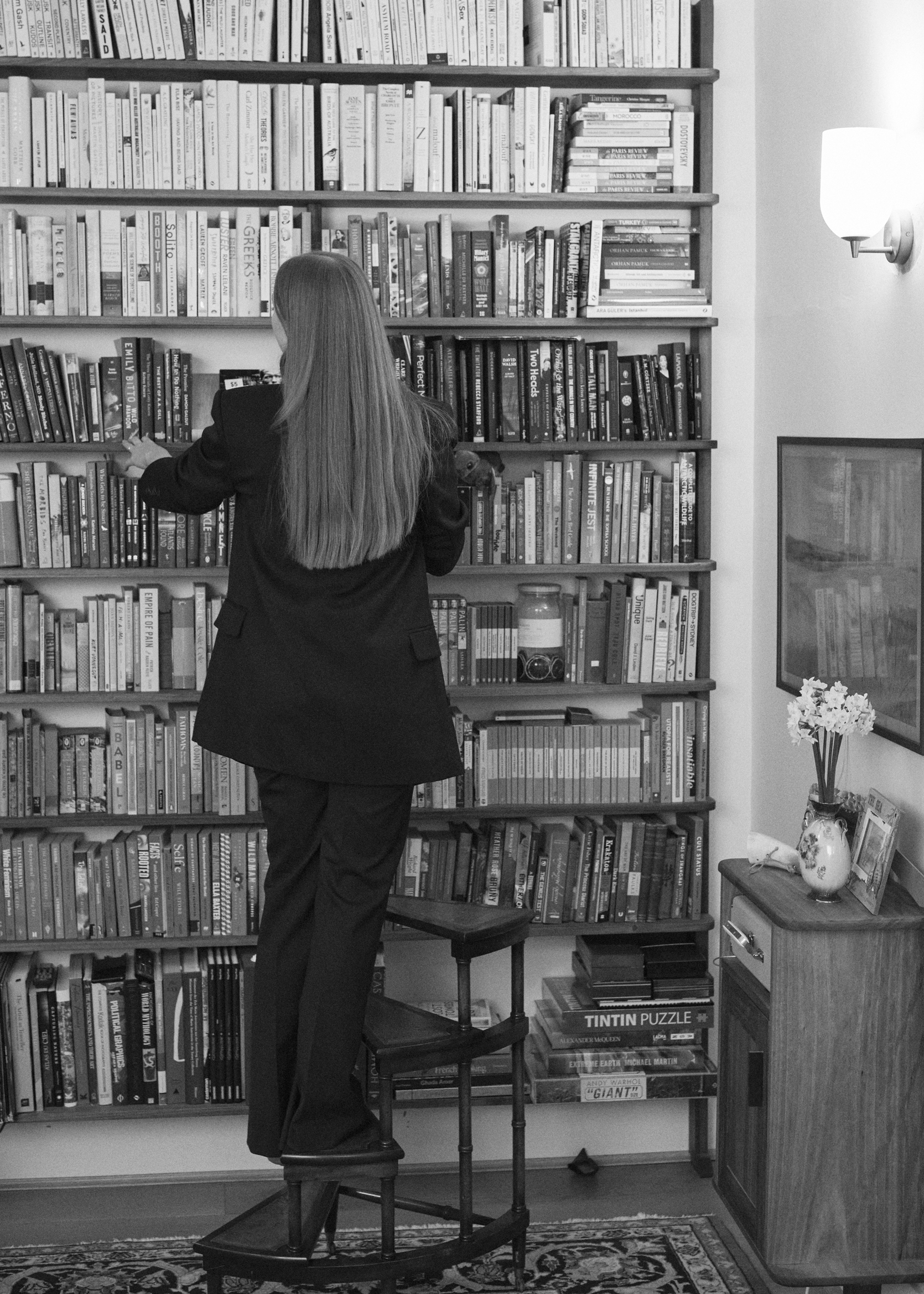

BL: I was always just a really big reader. I still believe that the most important work a writer can do is to read. I always loved reading and always loved books, but certainly all through high school, it never occurred to me that there was a chance that I could be a writer. To me, someone else did that. It’s interesting, to reflect on the limitations we can place on ourselves—and that is coming from someone with a background of extraordinary privilege.

For a little while I thought that I would be a journalist, I started my university years doing a journalism and arts degree and thought that I specifically wanted to be a photojournalist. But I did a year of a journalism degree and it was abysmal. I remember really clearly, I was with a cohort of about one thousand first-year undergraduates, and we had these lecturers who had been out of the industry for a while and were so cynical about the ‘internet.’ It was made out to be this big scary, unknown beast that would swallow up all the jobs. We were told there wouldn’t be any more jobs, that the golden days of journalism were dead.

I just thought, I do not want to spend four years of my life learning this from these people. So I switched across to law and really loved it—well, love-hate. But law is all about stories. People only get to the point where they are dealing with the law if they have fully conflicting, competing interests that they haven’t been able to solve themselves, both in criminal and civil law.

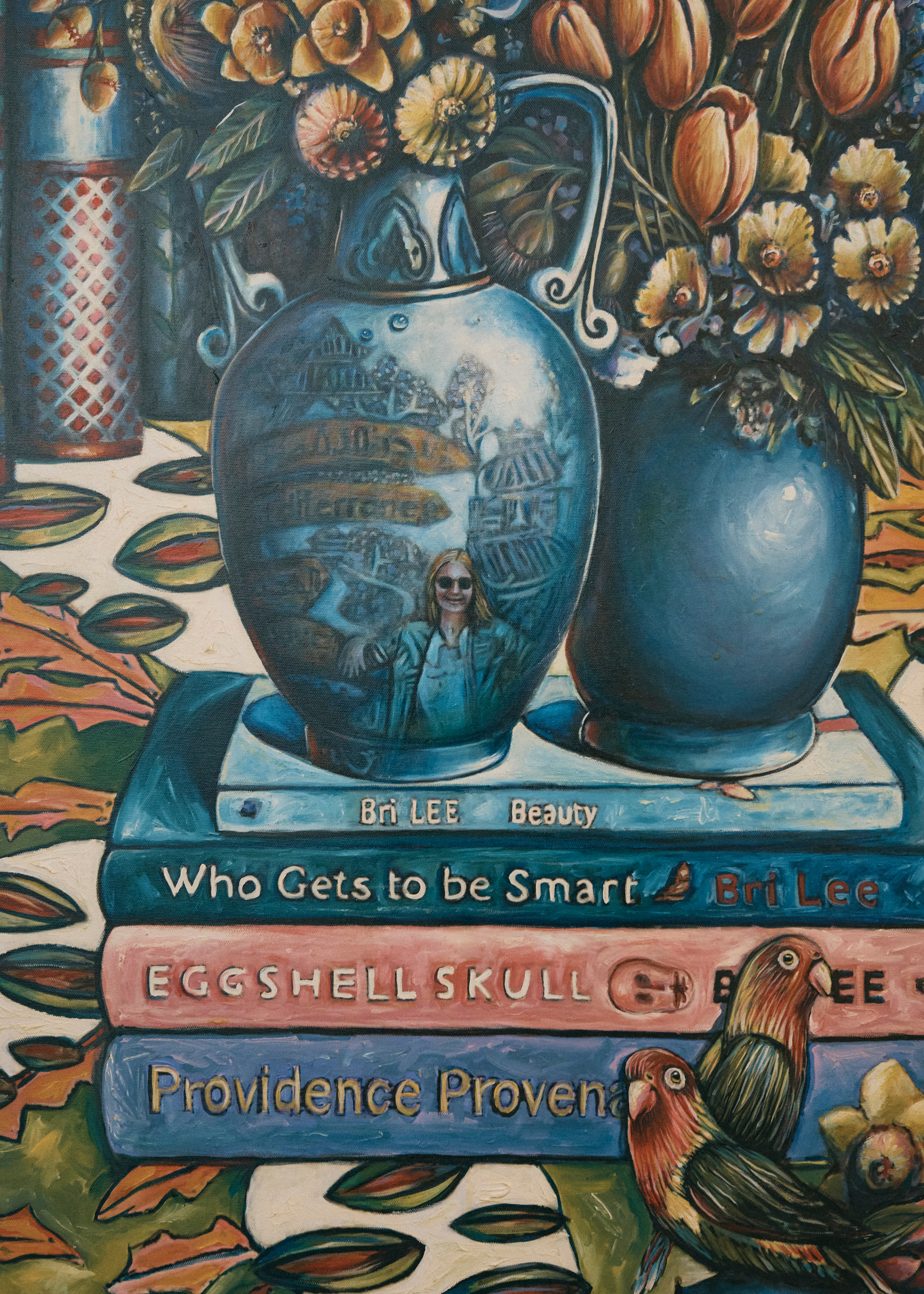

Eggshell Skull, the memoir I wrote, tells the story of how I certainly thought that I would be a lawyer, and then got pushed out of the industry for complicated and traumatic reasons. I wrote Eggshell Skull, and it came out in 2018. Nobody expected it to do well because I started writing it before Harvey Weinstein and before Me Too. But the year that came out was just, the year, and even the month that the world’s ears were open to that conversation in a way they hadn’t been before. Eggshell Skull was successful enough and I had been freelancing a bit in between, so it was then that I knew I would be able to make a go of this whole profession.

Now, I do a lot of different things. I freelance, then I have whatever book I’m working on, and whatever book is coming out next, and then I have the newsletter and now I have the podcast. It’s a lot, but I absolutely love it. I definitely feel like I’m doing my dream job.

U: Is the work you do across mediums symbiotic or complementary?

BL: I think they are complementary. I’m also doing my law PhD and every time I have to switch between different types of writing, it helps me further clarify the different strengths and demands that each need of me. Often I will begin my day writing chatty, first-person, conversational, quippy content for my newsletter, then switch in the afternoon to case summaries for my PhD. I find that sometimes the contrast between the modes helps me move between them, and makes each one stronger because they’re so different. They are also symbiotic in a more cumulative sense. My business now and the work I do, in a way, is being Bri Lee, and within what I bring to any given book, podcast episode, newsletter edition, or appearance on The Drum—even an investigative journalism piece in The Monthly—there are maybe a dozen areas of expertise and interest I have that overlap and inform each other. So yes, there is a way in which all these different modes of writing complement each other and help me draw connections between things. That is work I do that I think people value, and also work that I find deeply satisfying.

U: What kind of stories do you feel you have an obligation to tell?

BL: I think I have quite a juvenile response of seeing or hearing something and thinking, ‘that’s not fair!’ That’s a pretty big catalyst. But I think I’ve always been interested in how individuals and systems interact. I look at how humans create systems and how other humans are affected by those systems. I think about whether or not something’s fair, or whether it makes me mad. Unchecked power will self-perpetuate. The people who are ‘untouchable’ will become more untouchable if a light is not shone on their misconduct.

It is something that I care about. It makes me feel good to do that work, in many ways, shapes and forms.

"I still believe that the most important work a writer can do is to read."

~ Bri Lee

"I still believe that the most importantwork a writer can do is to read."

~ Bri Lee

U: You’ve written about fashion, and have investigated certain practices in the fashion industry through your journalism; namely the investigative piece, Pret a Porter, that you wrote for The Monthly. I think you dared to tell a story that many others were too hesitant to confront in the way that you did.

BL: When I reported the Ellery piece, people I spoke to said that this story was an ‘open secret’ in the industry. What’s really interesting to me is that when the revelations came out about former high court judge Dyson Heydon having sexually harassed six of his judge’s associates, people referred to it as being an ‘open secret’. Obviously, I’m not conflating the two sets of behaviour in any direct way, but what I do think is analogous is how it often takes a village to enable unethical behaviour of any kind. People are afraid—sometimes validly and sometimes invalidly—of repercussions, of speaking out. In both of those examples—not that I had anything to do with breaking the story about Dyson Heydon, but I certainly have spoken a lot about it in the aftermath—I don’t need to appease anyone. I no longer need to please anyone in the legal industry because I’ve already sort of burned that bridge, happily. I also don’t have to please anyone in the fashion industry. I think the actual people who put their skin in the game for the writing of that Ellery piece were those makers who are willing to talk to me on the record. I was just honoured that they trusted me with their stories.

U: It’s evident in the piece that there’s a genuine sense of integrity and a desire that’s beyond yourself to tell an important story and to do the right thing. I think that resonates with people—both those who spoke to you and the readers alike.

BL: I do think that readers typically have good bullshit detectors. Readers can tell when you’re writing a puff piece or when you’re sort of pulling your punches. People know.

I would also like to give a shout-out to Michael Williams and The Monthly here. They paid for the piece to be translated into Mandarin so that I could print it out and take it to the makers. That’s a really critical part of my feelings of obligation towards doing the right thing by that story. I would have paid for that if The Monthly didn’t, but it’s thousands of dollars to get an eight thousand word article properly translated.

Anyway, I went to the Wong’s on the same morning that I saw a show at this year’s Australian Fashion Week in the afternoon. It was shocking for me going to Fashion Week this year, having just finished reporting this piece, seeing how deliberately a lot of the industry tries to keep itself separate and artificially sectioned off from the reality of the rest of the industry. I just have the clearest image in my mind of the factory of women, most of whom are from migrant backgrounds, working, hunched over sewing machines. Then seeing a show that afternoon where there is just such a deliberate way that their real and meaningful and valuable labour is deliberately made invisible.

U: There’s a huge dissonance. Which highlights even further the urgency of your reportage. Tell me about some of the other projects you’re working on at the moment.

BL: I’ve been running my Substack News and Reviews for two-and-a-bit years now, but what I’ve just started doing that I’m really excited about is a monthly News and Reviews Magazine where I pay fantastic contributors to write for me. It’s going really well. When I started my Substack—which is normally a weekly dispatch straight from me—I remember thinking to myself that Substacks were already huge in the U.S. and UK and that if I started then, in 2021, I would be just getting ahead of the curve of them going big in Australia too. But I didn’t have any luck. I know from statistics, that I have been one of about a dozen people leading the charge, trying to get Substacks understood, respected, appreciated, celebrated, and enjoyed in Australia. What I thought was going to happen last year has started happening this year; it’s starting to take off here in a way that it previously wasn’t. So it was good timing in the end. Now News and Reveiws still goes out every week, but on the first Wednesday of each month, I run News and Reveiws Magazine. It’s got brilliant people writing for me on basically whatever topic they have a unique perspective and a lot of passion about. The response was really fantastic to the first one I just did in August, and the next one’s coming in September, and it’s even better.

"If you're doing work that you feel is important, it will be impossible to have everybody like you."

~ Bri Lee

"If you're doing work that you feel is important, it will be impossible to have everybody like you."

~ Bri Lee

U: Why do you think that the Substack delivery format has resonated with so many people, first overseas and now finally in Australia?

BL: I can say why I think we have been slow on the uptake here. It’s because Australians culturally have a mental barrier around paying creatives directly for their work, instead of paying a masthead, or a company for a feeling of more legitimacy. There is just something cultural in Australia — it’s been part of a lazy narrative for so long now – that artists are not contributing legitimately or working as hard. Whereas in the U.S. and UK, I think one of the reasons it works more overseas is because they have less of the tall poppy thing that we have really badly in Australia. But also because they have more of a celebrity thing than we do here. Substacks in the U.S. particularly have sort of fan-base followings, which is a vibe I don’t necessarily like. So, pros and cons. I want people to subscribe to News and Reviews because they value what it brings them every week.

U: What is it like to you to see the work you have produced, or projects you have been involved in, fully realised, published and put into the world, and then engaged with?

BL: It’s a little bit different with the different types of work I do. When I’m on book tour, when somebody turns up to the signing desk and they have the oldest and most battered, bruised, dog-eared copy of one of my books and they tell me it’s passed between half a dozen of their friends—that is the ultimate. That’s the dream; to know that something you’ve made has created space for conversation and exchange of ideas and experiences between other people when you’re not even there anymore. I place a lot of value in that and I know my work has done that.

There is also the bad side where I have copped hate. If you are speaking or writing about things that are important to you, it is impossible to do so whilst having everybody like you. Especially if you’re a woman. People are far less willing or able to separate your ideas from yourself, especially if you are commentating in public, as a woman, and tenfold if you’re a person of colour.

But what I really like, for example, is a piece in News and Reveiws Magazine that Kieran Pender—who’s phenomenal—wrote about how there has been a significant uptake in recent years in women’s sports, and that the viewership statistics for the World Cup at the moment are through the roof. Kieran’s been a sports journalist for about a decade, and he’s looking at the demographic of sports journalists in particular, where it’s overwhelmingly men, and looking at how women’s sports should be covered. He considers the competing factors about how to do it best moving forward, because we don’t want women’s sports to feel like thy are only for women, whereas ‘regular’ sports, i.e.men’s sports, are for everyone. You don’t want to have that siloing effect, but equally, you want the increase in public appetite for women’s sports to have a flow-on to better roles and opportunities for female journalists. So Kieran’s written this piece all about these competing interests, and it’s really nuanced. I don’t know anything about sports; I ran the piece because of the gender and media aspects, and how fascinated I am by these nuanced perspectives. In the comments section, people are genuinely replying to each other about examples and give-and-takes in the industry. It is so gratifying, specifically with the newsletter, that I feel like I’ve created a space where people are capable of having nuanced conversations on any given issue.

U: It is heartening to know that there are nuanced comment section conversations and readerships that are participating in discourse for all the right reasons.

BL: Yeah. It’s been a very long time since I have felt like that was possible on social media.

U: Do you hold any fundamental values or philosophies that have guided you during your life and work?

BL: Something I had to learn the hard way, which I mentioned before, is that if you’re doing work that you feel is important, it will be impossible to have everybody like you. I think that’s probably true in most fields. If you are fighting for what you believe in, in any shape or form, the people who benefit from the status quo will come for you, in some way or to some degree. What has helped me, and what I keep trying to come back to, is that I only need to be liked by the people who I actually know and love and trust. As a human being – let alone as a writer or a public person or creative in general – I cannot afford to worry about whether or not thousands of strangers like me. If you are worried about whether or not people like you, it’s going to stop you from doing bold work. Then the huge pull in the opposite direction that you have to keep in mind is that if you fuck up, you have to be accountable for that. It’s not as simple as saying, ‘I’m never gonna listen to criticism.’ You have to somehow be willing to learn and be accountable if you do make mistakes because everybody does. The thing I’ve had to learn the hard way, and I think will probably be learning for the rest of my life, is how to differentiate valid from invalid criticism. I also think that women in particular, waste so much of their lives worrying about whether or not everybody likes them. I can’t tell you how liberating it is once you let go of that.

U: You almost have to learn to turn your back on the –

BL: —the expectation of palatability.

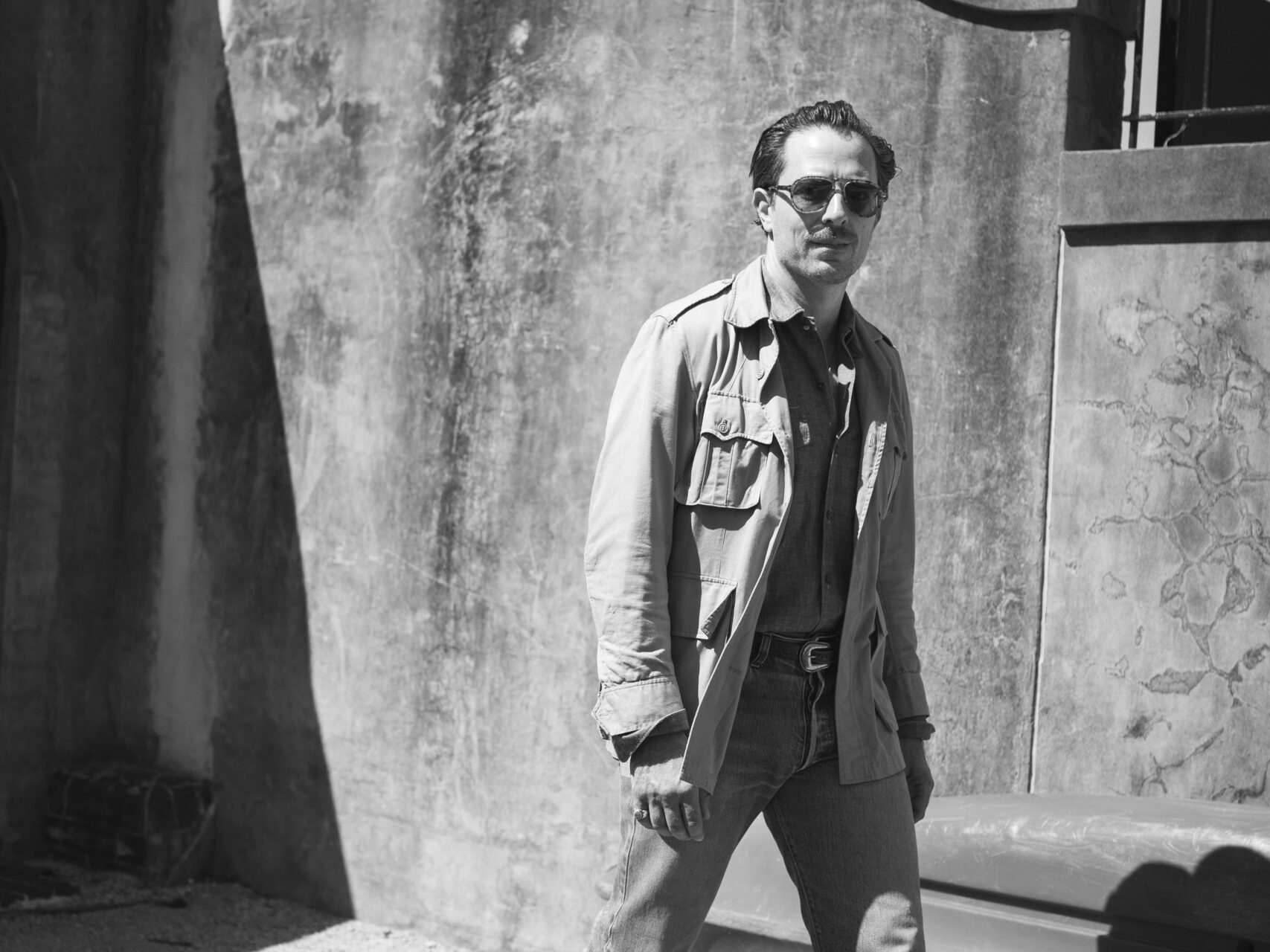

Interview and profile by Magdalene Shapter

Photography by Peter van Alphen

Wardrobe courtesy of CAMILLA AND MARC and bassike

Styling by Jessica Blaise Williams for UMENCO